Mostek’s 16K MK4116 and its 64K successor, the MK4164, became the DRAMs that defined late-1970s and early-1980s microcomputers and set conventions the industry followed for years.

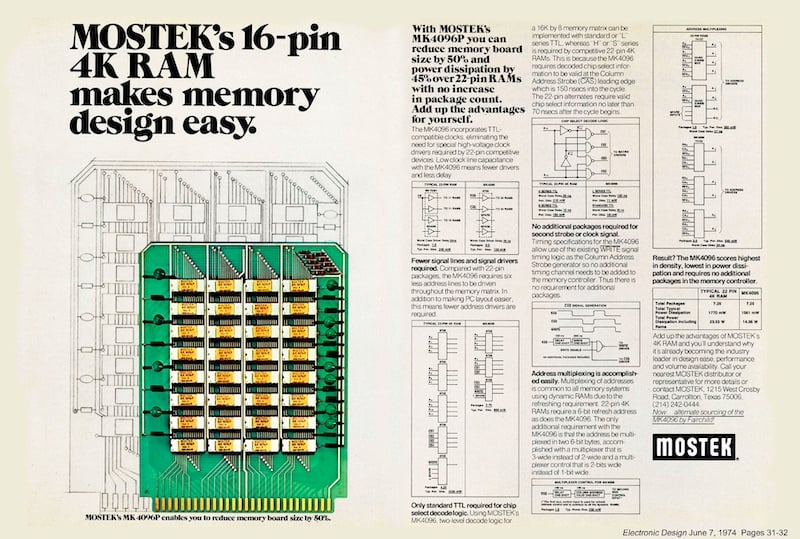

In the second half of the 1970s, system memory was changing fast. While Intel’s 1103 had already shown that DRAM could displace magnetic core, scaling 1-Kbit memories to something useful for microcomputers required both better cell design and a more approachable interface. Mostek delivered that with the MK4116, a 16-Kbit DRAM that paired a dense one-transistor cell with the company’s now-legendary address-multiplexing scheme.

At its peak, the MK4116 held more than 75% of the global DRAM market share. Image used courtesy of Makers Electronics

A few years later, the MK4164 extended the formula to 64 Kbits and eliminated the multi-voltage headache that had accompanied early DRAM. Together, they became the de facto RAM architecture for the first wave of consumer micros and early PCs.

The 16K DRAM That Became Everyone’s 16K DRAM

When Mostek introduced the MK4116 in 1977, it entered a market still feeling its way through the realities of dynamic memory. Designers had just spent years wrestling with the 1103’s timing margins and external refresh logic. The MK4116 solved two major problems at once by offering a straightforward RAS/CAS protocol and packing 16 Kbits into a standard 16-pin DIP by multiplexing row and column addresses on seven shared pins.

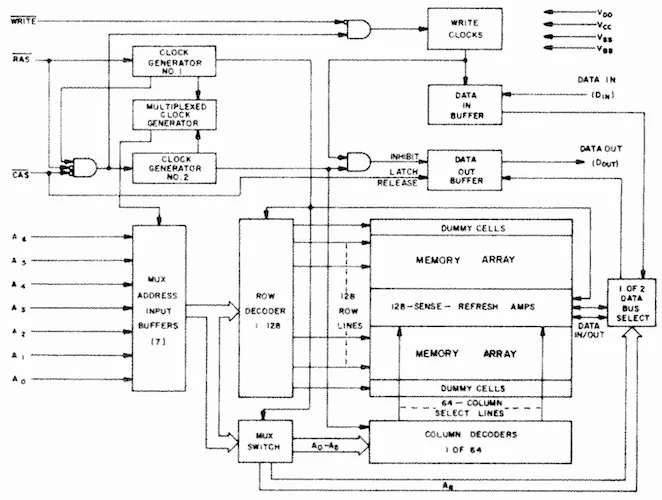

At the transistor level, the MK4116 used a single-transistor dynamic cell with precharged bitlines and a central bank of sense amplifiers. Internally, it was arranged as a 128×128 matrix, refreshed row by row. Page mode—holding the row active while stepping across multiple columns—gave systems a welcome throughput boost at a time when microprocessors were still slow enough for DRAM cycles to matter.

Functional diagram of the MK4116. Image used courtesy of Wiki Console

But this simplicity came with a power catch. Like the Intel 2708 EPROM that appeared in the same decade, the MK4116 required a three-rail regime of +12 V, +5 V, and -5 V. In hobbyist micros, these rails often came from aging linear regulators or DC-DC inverters, and a missing -5 V supply was enough to destroy a full bank of DRAM.

Regardless, it shipped in staggering volume. Apple II boards were filled with Mostek 4116s; Sinclair’s early Spectrums used them in the lower 16 Kbits; Commodore and Tandy machines adopted them; and arcade hardware from Williams and Atari depended on them for frame buffers and game logic. In practice, “16K DRAM” meant “4116-compatible DRAM.”

Mostek’s NMOS process helped here, too. Despite being dynamic internally, standby power was low enough for compact systems, and the company’s double-poly approach produced a memory cell with strong enough margins that second-source vendors had no trouble cloning it. The MK4116 became not just a product but an architecture that other companies reproduced pin-for-pin.

From Three Rails to One: The MK4164 Era

The industry’s next step was obvious. Home micros were pushing beyond 16 Kbits, IBM was preparing the PC, and system designers wanted to eliminate the multi-voltage baggage that earlier memories dragged along. Mostek’s answer was the MK4164, a 64-Kbit DRAM with a single +5 V supply, an internal substrate-bias generator, and timing compatible with the page-mode conventions already baked into existing controllers.

The MK4164 expanded the address bus to eight multiplexed lines, internally mapping the array into 128 rows and 256 columns. Sense-amp banks doubled in width but retained the same dynamic operation and the RAS-driven refresh pattern designers were used to. As with the transition from the 2708 to simpler, single-supply EPROMs, shedding the extra rails didn’t just simplify power requirements, but it also made boards cheaper and more reliable.

An ad for Mostek's MK4096P, a predecessor to the MK4116 and MK4164. Image used courtesy of Wikimedia Commons (Public domain)

Speed bins ranged from roughly 120- to 150-ns, fast enough for the 4.77-MHz PCs and 8-bit micros that adopted it. And while the earlier 4116 had taught system designers to fear power sequencing, the MK4164 finally behaved like the clean, drop-in logic-level DRAM the industry had been waiting for.

Unfortunately for Mostek, the transition from 16 Kbits to 64 Kbits was also the moment Japan’s memory manufacturers surged ahead. Mostek had pioneered the multiplexing trick that made 16-pin DRAM viable, but its 64-Kbit ramp slipped, and the price war that followed crushed its margins. The MK4164 still sold extremely well, populating countless PC 5150 boards and becoming a staple replacement part, but by the time the 256-Kbit generation arrived, Mostek’s window had closed.

A DRAM Legacy Written Across a Generation

Viewed today, the MK4116 and MK4164 sit in the same historical lane as the 1103, the µA741 op amp, the 2708 EPROM, and RCA’s CD4000 logic family. Each solved a practical design problem so effectively that it became the default choice for a generation of engineers.

Their real achievement wasn’t just density, cost, or the cleverness of multiplexing. It was standardization. They taught hardware teams what DRAM should look like, how it should behave, and how memory controllers should talk to it. The conventions Mostek set still echo today in the logic that underlies modern SDRAM and DDR devices.

And they powered an era—the micros in classrooms, the boards in arcades, the kits on workbenches, and the early PCs that took computing into the mainstream. Few chips can claim that kind of ubiquity. Fewer still did it with only a single bit per package.